What Does The Relief Bill Do To The Deficit?

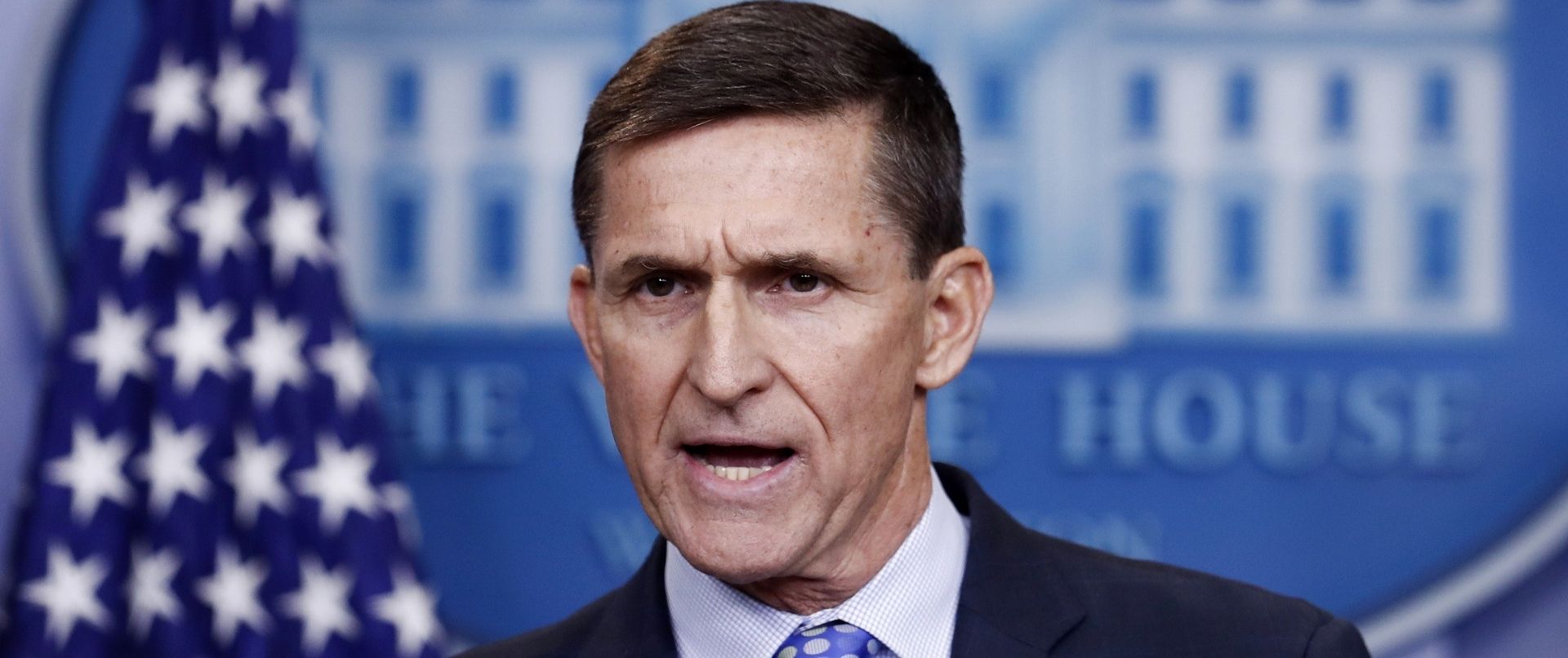

Republican senators who want to keep the price tag of the next coronavirus relief package from ballooning are increasingly skeptical that Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin will hold the line on spending without close supervision.

Complicating matters, though, is the fact that Senate Republicans themselves are divided over how big the next package should be. GOP lawmakers who want to go over $1 trillion in new federal aid say they don’t have any problem with Mnuchin taking the lead.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, sensitive to concerns about the rising deficit, says he wants to keep the forthcoming relief package at the $1 trillion mark.

The Senate GOP leader and his allies — Senators Richard Shelby, Roy Blunt and Lamar Alexander — have spent this week working with Mnuchin and White House chief of staff Mark Meadows to reach a unified Republican position before starting talks with Democrats.

Those GOP talks appeared to stall Thursday afternoon when negotiators left Capitol Hill without releasing text of the Republican proposal despite proclaiming earlier in the day they had a “fundamental” agreement.

Senate Republicans familiar with the talks say their goal is to make sure Mnuchin doesn’t get ahead of their conference when he enters negotiations with Speaker Nancy Pelosiand Senate Democratic Leader Charles Schumer.

Mnuchin, Meadows and National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow are taking the lead for the White House.

Mnuchin, a former Goldman Sachs executive, is a trusted member of Trump’s inner circle, having known the president for 15 years. He served as Trump’s 2016 campaign finance chairman and eventually was tapped as Treasury secretary. He is one of the few original Cabinet secretaries who remain in the administration.

The Treasury secretary has compiled a record of success working with both parties in Congress on major pieces of legislation, including the record $2.2 trillion CARES Act passed in late March. He was also instrumental in striking deals to raise the debt ceiling and settle budget negotiations in 2019, and was intimately involved in passing tax reform in 2017 when Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress.

His role in crafting the last relief package demonstrated his ability to foster a working relationship with Democratic leadership despite sky-high tensions between Trump and House leaders following the president’s impeachment. Mnuchin spoke to Pelosi multiple times a day during the negotiations in March for the CARES Act.

Mnuchin’s supporters in the Senate GOP conference say he’s the administration’s most effective negotiator and is most likely to get a result.

But some conservatives are wary of Mnuchin’s role in discussions involving COVID-19 relief spending, expressing concerns he may give too much away to Democrats in negotiations.

Senate conservatives predict a deal with Democrats is likely to swell to $1.5 trillion to $2.5 trillion dollars, an amount closer to the $3 trillion HEROES Act passed by House Democrats in May.

Senator Rand Paul on Thursday says he has “zero” confidence in Mnuchin holding the line on spending in negotiations with Democrats, making a zero with his thumb and fingers for emphasis.

“They’re starting at a trillion dollars we don’t have, we’re going to have to borrow, and they’ll wind up at a trillion and a half or 2 trillion,” he said. “They are willing to compromise with their principles on deficits to begin with.”

“They’re going to just give up completely when they talk with the Democrats and they double the amount of debt,” he said.

Many Republican senators were outraged by the deal Mnuchin negotiated with Pelosi in mid-March that required employers to provide 14 days of paid sick leave at not less than two-thirds of regular pay rates. The bill was met with indignation among Senate Republicans who complained they were cut out of the talks.

When Mnuchin spearheaded the talks on the subsequent bill that became known as the CARES Act, Senate Republicans felt they were largely left out of the loop on key concessions to Democrats — principally the decision to provide $600 a week in federal supplemental assistance to state unemployment benefits. Some Republicans also criticized the allocation of state and local aid, which they thought was disproportionately allocated to large cities.

Other GOP senators say they’re glad Mnuchin is leading the negotiations for the White House and raise doubts whether McConnell or anyone else in the Trump administration would be able to strike a deal that the president, Senate Republicans and congressional Democrats would support.

“Somebody’s got to bridge that gap between these three parties and I don’t know anybody better to do that,” said a Republican senator who requested anonymity to discuss Mnuchin’s role.

The senator said the view of Mnuchin is “generally positive” in the Senate Republican conference while acknowledging “there are” also GOP colleagues highly skeptical of Mnuchin’s willingness to take a tough enough line with Democrats.

Mnuchin and Meadows form an odd couple. Mnuchin is not seen as firmly tethered to any political ideology while Meadows established much of his reputation in the House as chairman of the Freedom Caucus, a staunchly conservative group of lawmakers.

Meadows told reporters earlier this month that Mnuchin would be leading the negotiations on the next coronavirus relief bill. He said the Treasury secretary had done an “outstanding job” in earlier COVID-19 relief negotiations and noted that the two of them talk frequently, sometimes on “an hourly basis.”

Some Senate Republicans, however, think McConnell needs to keep close tabs on Mnuchin to make sure the next package doesn’t get stuffed with Democratic priorities or stray too far beyond the $1 trillion mark.

“I’ve personally been concerned that we’ve left too much of the congressional negotiation up to the White House,” said a second Republican senator who requested anonymity to discuss Mnuchin’s role in the negotiations.

“The $600 thing, we felt totally left out of that. The state and local money was so poorly divided up among the states,” the lawmaker added of concessions the White House made to Pelosi and Schumer earlier this year that left Republican senators disappointed.

“I think it’s hard for somebody who’s never done this before to negotiate head-to-head with someone who’s done it a hundred times,” the source said.

The Treasury Department did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Mnuchin’s GOP critics don’t think he is sufficiently attuned to the politics of their base, which includes a large contingent of fiscal conservatives, when he negotiates with Democrats.

“[Mnuchin is] really good at finance, so he looks and says: What do we need to make sure the stock market is OK?” said David McIntosh, president of the conservative Club for Growth. “But he’s not really aware of what it takes for small businesses to reopen.”

McIntosh said he was no fan of the federal unemployment insurance provision Mnuchin allowed to be included in the CARES Act. Many Republicans argue the $600-a-week increase in unemployment benefits served as a disincentive for people to return to work.

For deficit hawks like McIntosh, they feel somewhat comforted that Meadows is one of the other lead negotiators for the administration.

“The good thing about Meadows and his experience on the Hill is he knows sometimes you’ve got to fight for principle even if it means you might not get the bill done,” McIntosh said. “Then, you take the principle to the voters.”